HIST4702 (2023-24) Digital History Project: 火攻挈要

Comparison with Works in the Post-Opium War Period

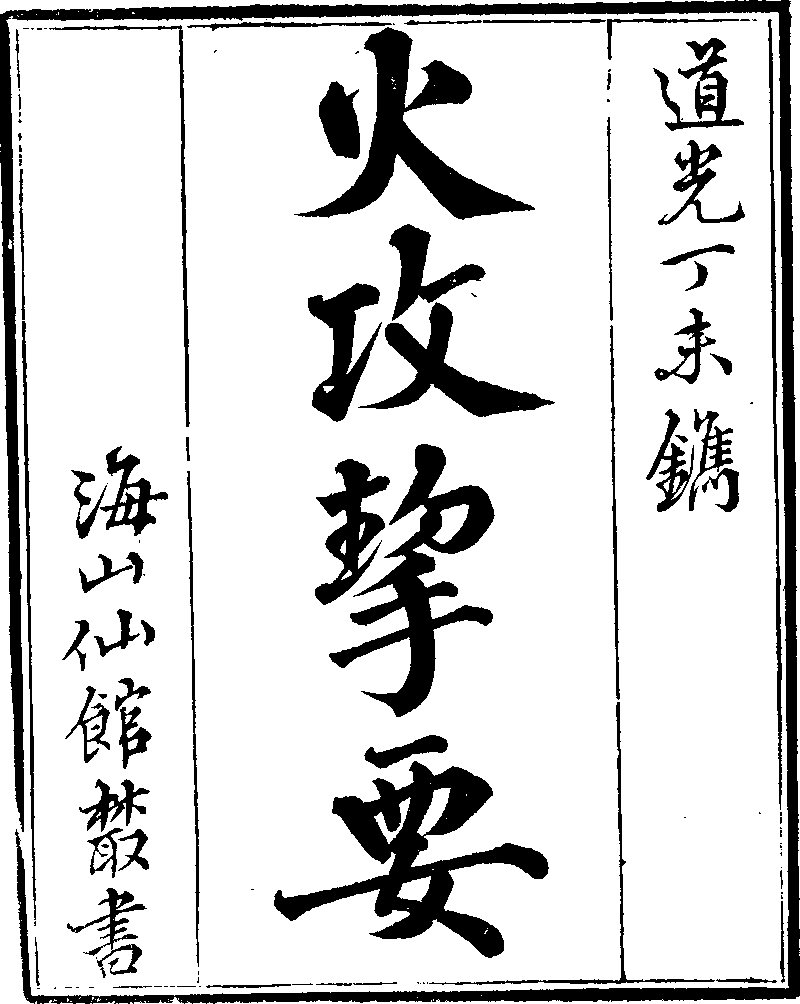

After the Ming-Qing transition, Huo gong qie yao lost its timely prominence until the crisis in the late Qing era after the First Opium War (1839-42). Hence, we compare Huo Gong Qie Yao with works by Gong Zhenlin龔振麟 (1796-1861), Wang Zhongyang汪仲洋 (fl. 1780-1845), and Ding Gongchen丁拱辰 (1800-1875), all of whom were military scientists specializing in artillery and authors of military essays stimulated by Qing’s shameful lose in the Opium War. It is noteworthy that all three authors had pored Schall’s book, as was revealed in their writings, before the more widely circulated reprint in 1847 (海山仙館叢書本) sponsored by millionaire Pan Shicheng潘仕成.

Gong, Wang, and Ding’s works were included in Wei Yuan魏源(1794-1857)’s prestigious gazetteer, Hai guo tu zhi海國圖志(Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms, 1843-1852), in its 60-volume edition published in 1847. Wei Yuan compiled this masterpiece in response to Qing China’s ignorance of world issues before the Opium War. (*The OCR text of Hai guo tu zhi in CTEXT is the enriched 100-volume edition first published in 1852.)

① First, we selected Gong Zhenlin’s Zhu pao tie mo tu shuo 鑄炮鐵模圖説 (Illustrated Guide of Iron Mold for Casting Cannon, 1842) for comparison. This essay is in Vol 86 of Hai guo tu zhi.

However, after comparison, we found the two texts indeed share some similarities but merely on a sporadic basis (e.g. proportional calculation of casting a cannon“比例推算”). That can be explained by Gong Zhenlin’s complaint about Adam Schall’s work for its impracticability in the same essay:

“Adam Schall from the Far West had authored a two-volume book, Huo gong qie yao, on artillery. It is an elaborated and detailed book, but its methods of building furnaces and casting molds are even harder and more complicated than the practices in the interior of China” 惟泰西湯若望火攻挈要秘要兩卷,專講炮法,頗為詳備。然其建爐造模之繁難,甚於內地。(Hai guo tu zhi, Vol 87)

② Then, we compared Vol 87 of Hai Guo Tu Zhi with Huo gong qie yao. This volume includes an essay, Zhu pao shuo鑄炮說 (On Casting Cannon), by Wang Zhongyang汪仲洋, a magistrate who served in coastal counties in Zhejiang Province during and after the Opium War and was interested in military science. In this essay, he commented that Adam Schall’s technique in building batteries was more difficult than the Chinese way but also highlighted its advantages. (其論築台砌窯建模諸法,似不若中國較為簡便。) Still, Wang’s essay cited many texts from Huo gong qie yao’s first and second volumes, especially the content dealing with proportional calculation (推例其法).

③ However, other artillery-related and fire attack-related works in Hai guo tu zhi (i.e. Vol 87-91) basically cited nothing from Adam Schall’s book, even though these volumes include multiple essays by Ding Gongchen丁拱辰(1800-1875), who was spellbound by Adam Schall’s book at the first sight that he later decided to publish a revised version of Schall’s book.

Ding named his book Zeng bu ze ke lu增補則克錄 (published in 1851) , meaning the supplement to “Ze ke lu則克錄” (Book of Invincible, Huo gong qie yao’s other name). Unfortunately, we failed to find either its hard copy in CUHK’s library or public domain E-resources, which meant that we were not supposed to put the text into CTEXT due to copyright issues. Nevertheless, we relied on the excerpt offered by the document delivery service. After a manual cross-reading, we found that the two texts are basically identical, but Ding Gongchen added a special chapter in which he annotated every sectional title in Schall’s book with his corrections in measurement, gunpowder formulas, and usage of weapons. We look forward to that researchers can do further comparisons of these two texts in CTEXT in the future.

Conclusion: Huo gong qie yao was re-read by Qing military reviewers right after the First Opium War more critically and practically. Examined and filtered by Qing military writers’ practical experience, Schall’s book was indirectly included in Hai guo tu zhi and thus integrated into the intellectual history of the late Qing era, two hundred years after its first edition.